Carnet. Issue 10

This week - Paradise Lost, Children of Men, a professor and her students, and V&A East Storehouse

Books & Film

Children of Men

The Big Picture - The 25 Best Movies of the Century: No. 22, ‘Children of Men’ | The Ringer | Listen to podcast

P.D James - The Children of Men | Backlisted | Listen to podcast

Cosy as a scalpel | London Review of Books | Read story

I find it hard to resist stories set in a dystopian version of our world, and Children of Men is one of the very best of them portrayed on screen and in print. The 1992 novel and 2006 film adaption both start with the same premise - what if no human babies had been born in over two decades?

The Ringer’s Big Picture podcast, in a series on the top 25 films of the century, gives a great overview of the story behind the film, and why it works so well on screen.

Backlisted is a podcast discussing books that are less read today for a variety of reasons (though the picks are often books of significant repute and success in their time).

Their episode on writer PD James’ The Children of Men, source material for the film, includes an excerpt from the novel that demonstrates the big ideas that James was grappling with:

These assuaging satisfactions are also bittersweet reminders of the transitoriness of human joy; but when was it ever lasting? I can still find pleasure, more intellectual than sensual, in the effulgence of an Oxford spring, the blossoms in Belbroughton Road which seem lovelier every year, sunlight moving on stone walls, horse-chestnut trees in full bloom, tossing in the wind, the smell of a bean field in flower, the first snowdrops, the fragile compactness of a tulip. Pleasure need not be less keen because there will be centuries of springs to come, their blossom unseen by human eyes, the walls will crumble, the trees die and rot, the gardens revert to weeds and grass, because all beauty will outlive the human intelligence which records, enjoys and celebrates it. I tell myself this, but do I believe it when the pleasure now comes so rarely and, when it does, is so indistinguishable from pain?

I can understand how the aristocrats and great landowners with no hope of posterity leave their estates untended. We can experience nothing but the present moment, live in no other second of time, and to understand this is as close as we can get to eternal life. But our minds reach back through centuries for the reassurance of our ancestry and, without the hope of posterity, for our race if not for ourselves, without the assurance that we being dead yet live, all pleasures of the mind and senses sometimes seem to me no more than pathetic and crumbling defences shored up against our ruins.

A later passage in the book shows for me how good James was at creating a feeling of latent horror in the ordinary landscapes of a world decaying in the absence of hope:

The mud‐grey sea heaved sluggishly under a sky the colour of thin milk, faintly luminous at the horizon as if the fickle sun were about once more to break through. Above this pale transparency there hung great bunches of darker‐grey and black cloud, like a half‐raised curtain. Thirty feet below him he could see the stippled underbelly of the waves as they rose and spent themselves with weary inevitability, as if weighted with sand and pebbles. The rail of the promenade, once so pristine and white, was rusted and in parts broken, and the grassy slope between the promenade and the beach huts looked as if it hadn’t been cropped for years. Once he would have seen below him the long shining row of wooden chalets with their endearingly ridiculous names, ranged like brightly painted dolls’ houses facing the sea. Now there were gaps like missing teeth in a decaying jaw and those remaining were ramshackle, their paint peeling, precariously roped by staves driven into the bank, waiting for the next storm to sweep them away. At his feet the dry grasses, waist‐high, beaded with dry seed pods, stirred fitfully in the breeze which was never entirely absent from this easterly coast.

The podcast includes excerpts of interviews with the author herself, material on her own biography and position in the literary establishment, as well as a commentary on what works and doesn’t in the book.

An essay in the London Review of Books surveys PD James’ literary career more broadly, and asks what opportunities The Children of Men’s setting and genre could offer that detective novels didn’t:

The Children of Men (1992), a dystopian thriller, might be seen as a bid to defy the necessary constraints and underlying optimism of the detective novel. What if the order on which her crime fiction rests were to collapse, and contemporary civilisation, with all its wrong-headed folly, turns out to be done for? What then will be the point of detectives, no matter how shrewd their insights?

Books

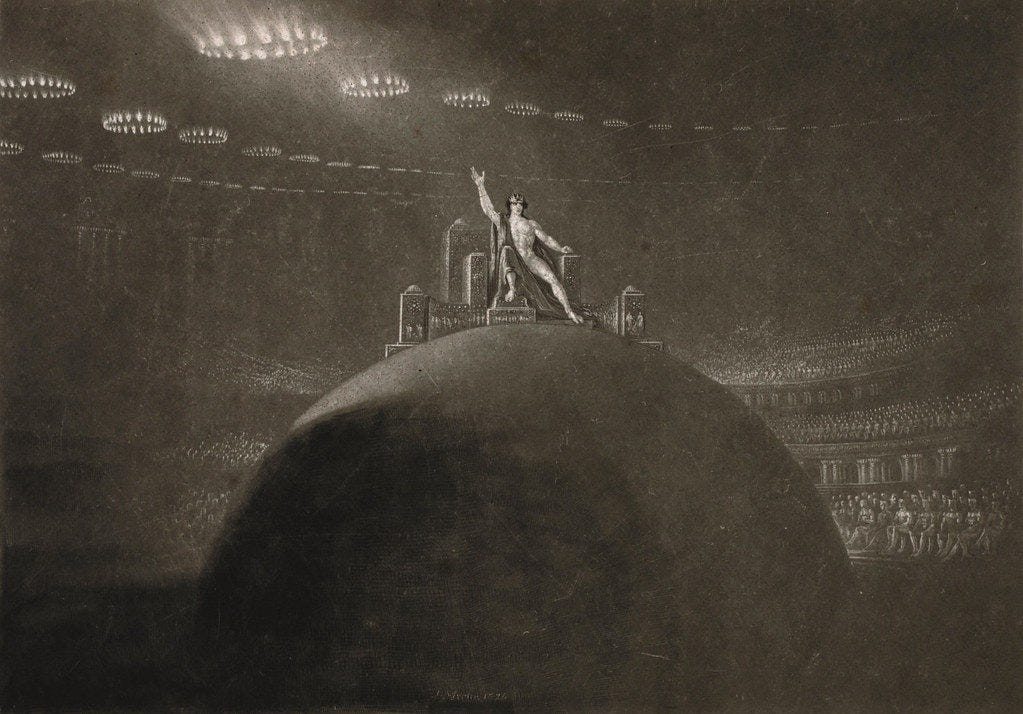

Reading Paradise Lost

The Sound and the Story | Public Domain Review | Read essay (2019)

This 2019 essay on the pleasures of reciting and reading Paradise Lost by the author Philip Pullman was a recent happy rediscovery. It is full of perceptive commentary on both the practice and benefits of reading and writing.

He writes about the power of reading a poem aloud before fully decoding its meaning:

The experience of reading poetry aloud when you don’t fully understand it is a curious and complicated one. It’s like suddenly discovering that you can play the organ. Rolling swells and peals of sound, powerful rhythms and rich harmonies are at your command; and as you utter them you begin to realise that the sound you’re releasing from the words as you speak is part of the reason they’re there. The sound is part of the meaning and that part only comes alive when you speak it. So at this stage it doesn’t matter that you don’t fully understand everything: you’re already far closer to the poem than someone who sits there in silence looking up meanings and references and making assiduous notes.

He also attests to the physical response poetry can elicit:

However, as I say, I was lucky enough to learn to love Paradise Lost before I had to explain it. Once you do love something, the attempt to understand it becomes a pleasure rather than a chore, and what you find when you begin to explore Paradise Lost in that way is how rich it is in thought and argument. You could make a prose paraphrase of it that would still be a work of the most profound and commanding intellectual power. But the poetry, its incantatory quality, is what makes it the great work of art it is. I found, in that classroom so long ago, that it had the power to stir a physical response: my heart beat faster, the hair on my head stirred, my skin bristled. Ever since then, that has been my test for poetry, just as it was for A. E. Housman, who dared not think of a line of poetry while he was shaving, in case he cut himself.

People

A Professor’s Final Gift to Her Students: Her Life Savings | The New York Times | Read story

This evocative essay in The New York Times tells the story of the intense and in some cases long lasting relationships between a university professor and her students, that ended with a transformative twist:

Over 50 years of teaching art history at New College of Florida, Prof. Cris Hassold had carved out an influential but complex legacy. She referred to her students as her children. She hired them to clean her home — a disturbing hoarder’s den. At times, she humiliated them in class.

But the students who knew her best described her as a singular force of good in their lives. “The cult of Cris,” as one described it, lives on in her 31 favorite students, who inherited her intensity, her quirks and, in the end, her life savings.

Art

V&A East Storehouse is a genuinely radical new museum | Financial Times | Read article

‘The national museum of absolutely everything’: new V&A outpost is an architectural delight | The Guardian | Read article

As a compulsive hoarder, a museum dedicated to showing off the previously offstage archive of a major national collection intrinsically appeals to me. The newly opened V&A East Storehouse has been acclaimed for shining a light on unseen treasures in the V&A collection, and for an inspiring and impactful design treatment.

V&A East Storehouse, a unique new cultural visitor attraction and working store, opened 31 May 2025, as part of East Bank in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, vam.ac.uk/east