Carnet. Issue 13

This week - Eileen Gray, Fred Goodwin, and AI-enabled digital notebooks

Theatre

Fred the Shred

The rise and fall of Fred Goodwin | Financial Times | Read story

Make it Happen | National Theatre of Scotland | Visit website

Hubris, crisis and scandal: how the NatWest ‘soap opera’ unfolded | The Guardian | Read story

The literary novel can’t compete in the age of Netflix | The New Statesman | Read story

A new play from Dear England author James Graham focuses on fallen banking CEO Fred Goodwin, who was at the helm when Royal Bank of Scotland had to be bailed out by the UK government in 2008.

Former FT editor Lionel Barber uses this as a springboard to tell the story of his career, and ask where responsibility for his failings ultimately lies:

At the heart of this tartan tragedy lies the question of human agency: was Goodwin a victim of forces beyond his control? Did cheap money and regulatory flaws fuel irrational behaviour by bankers worldwide? Or were individual character failings and an inbred corporate culture responsible for epic recklessness?

Barber’s story provides evidence of plenty of dramatic source material:

Meanwhile, hair-raising tales of bullying behaviour emerged. Daily management meetings were renamed “morning beatings”, where executives were ritually humiliated in public. Over dinner, Goodwin liked to invite colleagues to perform a turn. Informed that one senior RBS manager was out of the country and it was the middle of the night, Goodwin ordered him to be roused so he could remotely do an Elvis Presley act. Naturally, the victim obliged — to nervous titters all round.

The Guardian picks up the story of the taxpayer bailout of RBS and the lengthy process of sorting out the mess Goodwin left behind, which only concluded after nearly two decades, £10.5bn in taxpayer losses, and a series of executive defenestrations (including one precipitated by a kerfuffle over Nigel Farage’s banking arrangements).

Jason Cowley meanwhile has a nice anecdote in his opinion piece suggesting Graham and stage and screen writers like him are inheriting the mantle left vacant by the decline of the literary novel:

There was a revealing moment during Gareth Southgate’s BBC Richard Dimbleby lecture on 19 March when the camera settled on the playwright James Graham, who was among the invited audience. Graham smiled knowingly as Southgate made a joke about the striker Ollie Watkins being acclaimed “an overnight sensation” after he scored the winning goal in the semi-final of last year’s Euros in Germany. Watkins had worked his way up from the lower divisions over many years. Southgate is not a natural joke-teller and at times during the lecture, as he spoke about the psychological anguish he endured after his harrowing penalty shoot-out miss against Germany at Euro 96, one had the curious sense that Southgate was doing more than a passable impression of Gareth Southgate as portrayed by Joseph Fiennes in Dear England, Graham’s stage play that is being adapted into a film.

Fiennes-as-Southgate was more than a facsimile of the former England manager: he was part secular preacher, part self-help guru. Fiennes expertly captured Southgate’s mannerisms and speech patterns as he delivered his homilies about identity, resilience and belonging as if at a lectern. Premier Christianity magazine wrote approvingly that Southgate’s Dimbleby lecture had “the makings of a sermon” and not only because one of the lessons was about redemption. Has Southgate watched Fiennes-as-Southgate and learned from him? Has he read the script of Dear England? Or is it now impossible for Southgate watchers to see the man without also seeing Fiennes-as-Southgate? Small wonder Graham was smiling.

Design

Eileen Gray’s legacy

Eileen Gray | Heresies - Making Room: Women & Architecture | Read essay - online viewer or JSTOR PDF

Eileen Gray: Why now? | New York School of Interior Design | Watch panel discussion

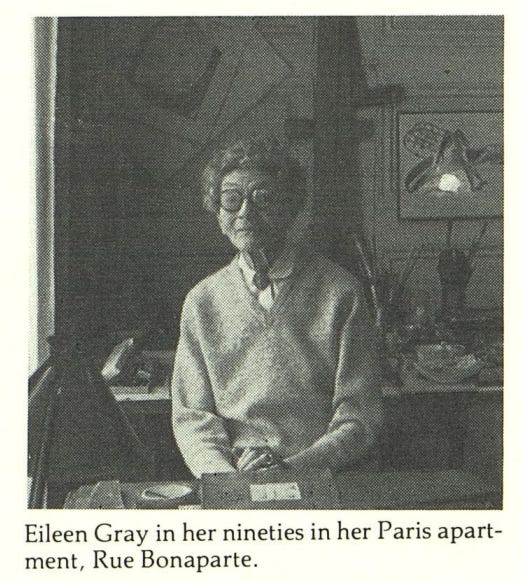

Eileen Gray: Pioneer of Design, December 1972 | The Architectural Review | Read profile

Eileen Gray was a major figure of 20th century design, forgotten for a period, now properly recognised, and the subject of a regular flow of documentaries, exhibitions, and other coverage. One of her most celebrated works was the house she designed and built in the 1920s in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, known as E-1027.

In the 1980s, Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Arts & Politics published an edition on Women in Architecture including an article on Gray and including a reprinted interview between her and her collaborator and partner Jean Badovici.

The interview is illuminating as to Gray’s process:

But how does one create the expression of an era and especially an era like ours, so full of contradiction, where the past has an influence in many ways and in which there are so many extreme points of view?

All works of art are symbolic. They interpret, they suggest the essential idea more than they literally represent it. The artist must find in this multitude of contradictory attitudes those which are the real intellectual and emotional underpinnings of the individual and the society at once.

For you, then, the architect must have a universal outlook?

Almost! But what is essential is that the architect understand the meaning of each thing and that the architect know how to be simple and sane, while not neglecting any means of expression. The most diverse types of materials are useful to express what the architect wishes of contemporary life. New materials, ludicrously employed, are as important in this as is architectural structure strictly speaking.

The article also speaks to how her work as a designer of furniture informed her practice:

Gray understood, in a detailed way, the use of an object over the span of a day or throughout the year, integrating this understanding into her work. In the broadest sense, then, “time” becomes a component of her analysis of functionalism. As a result, many of her objects have a quality of physical transformability that amplifies or extends the number of ways the objects can be used within the primary activity they serve.

A 1972 profile in The Architectural Review, written when Gray was in her 90s, was one of the first pieces of coverage to rekindle interest in her work.

The author concludes with this prescient passage on her late career and her impact:

But it was her choice to work alone and to concentrate on the quality of individual objects and on the remarkable refinement of detail. Her isolation has increased since the war. Her only executed project is an interior for her own occupation at St Tropez, but she has continued working on a number of ideas and is currently engaged on designing metal and plastic screens. She is even meditating on some pieces of furniture using plastic tube frames. Her interest in technique as well as in the changes of design has remained constant and she finds it tedious to reminisce. The curiosity of the young about her early doings seems extravagant, unwarranted, when so much is going on now to fascinate.

And yet the young will continue to be curious because however you estimate the scale of her achievement it is unique. Not only for the inventiveness and the high quality of the individual objects, but also because of that extraordinary fusion of formal invention with craftsman skill which required, at the time when she achieved it a visionary intuition about the possible grafting of invention on manual skill which only achieved a fully articulated and explicit expression in the work of the early Bauhaus masters.

Further reading

For those wanting to dive deeper, the documentaries released in 2016 (Gray Matters), and 2025 (E.1027: Eileen Gray and the House by the Sea) may be of interest. This recording of a panel discussion in 2016 entitled Eileen Gray: Why Now? also provides a good overview of the span of her work, with visual references scattered throughout.

Technology

Curated notebooks

Try featured notebooks on selected topics in NotebookLM | Google Blog | Read release

The World Ahead 2025 | NotebookLM | The Economist | Visit notebook

A barrier I’ve personally found with adopting generative AI tools over the last couple of years has been the sense that you are drawing from a vast range of unknown sources - and while some of those sources may be world-leading, others may be far from it. This was why I thought Google’s NotebookLM was interesting when I first tested it. The premise is that you curate the sources yourself, and then focus the tool’s abilities to parse, synthesise, and reformat on those specific documents. In addition to a typical chat interface you can create mind maps, structured documents, and even generate interactive podcasts based on the sources (I live in fear that these will soon be inundating LinkedIn).

Like all healthily funded generative AI plays, this service is rapidly evolving, and recent additions include suggested sources to augment your own picks and the ability to share your notebooks with others. This has now been added to by a series of public notebooks curated through partnerships.

It’s interesting to me the partners selected - namely bona fide old media stalwarts (The Economist, The Atlantic), prestigious academic-adjacent institutions (University of Oxford affiliated Our World in Data), and well established authors living (Eric Topol) and dead (William Shakespeare).

Nicholas Thompson, CEO of The Atlantic includes a comment on the launch that speaks to some of the future possibilities of this format:

The books of the future won’t just be static: some will talk to you, some will evolve with you, and some will exist in forms we can’t imagine now.