Art

William Kentridge

At home with William Kentridge, South Africa’s greatest living artist | The Financial Times | Link

William Kentridge: Artist Tour | Royal Academy | Watch video (from 2022)

Charles Eliot Norton Lectures - “Six Drawing Lessons.” | Mahindra Humanities Centre, Harvard University | Watch lectures (from 2012)

The Financial Times has an interview with the South African artist William Kentridge. Kentridge had a well received show at the Royal Academy in 2022, the video embedded below is his walkthrough of the exhibition. The 70-year-old’s activity remains prodigious in 2025, with ‘Oh To Believe in Another World’, an animated film inspired by Shostakovich’s Symphony No.10 showing in a live musical performance in London earlier this month, and works being exhibited at Hauser & Wirth New York and Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

In the Financial Times interview Kentridge outlines the need for a “gap” or “lack” as an artist:

Although his output is prolific, Kentridge questions his own sense of creative fulfilment. “The harder part of being an artist is that you need to have a gap, you need to have a lack,” he says. “If you’re satisfied, if you’re fine as yourself, then you can just get on with your life. You don’t need to keep on making all these millions of…” – he mimes scribbling the same rapid, sweeping strokes that appear in his animations, “that you need other people to look at.”

And he expands on his creative process:

But he has allowed doubt to become part of his creative process. “The first idea you have when you’re doing a project seems such a clear, good idea, and then as you work on, it’s not quite so good,” Kentridge continues. He’s talking about creativity itself, of course, but also the grand ideas of the 20th century. “Then, you’ve got a choice of either becoming more and more certain, and more and more strident, or else you can accept that it doesn’t work and that you need to find new ideas from the cracks,” he says. “What is the push to make something that’s beyond yourself, that remains when you step away from it?”

For anyone who wants to dive deeper into Kentridge’s work and methods, the full series of six lectures he delivered at Harvard University’s Mahindra Humanities Institute in 2012 entitled “Six Drawing Lessons” are available on YouTube.

Film

The tastemakers

A24 Movie Browser | Information is Beautiful | View interactive chart

How A24 took over Hollywood | Vox | Watch video

A simple but effective data visualisation on the catalogue of the much hyped film studio A24 caught my eye. The pleasing infographic displays the A24 catalogue as it was in November last year, with films sized by revenue information about their critical and audience ratings, as well as genre and director.

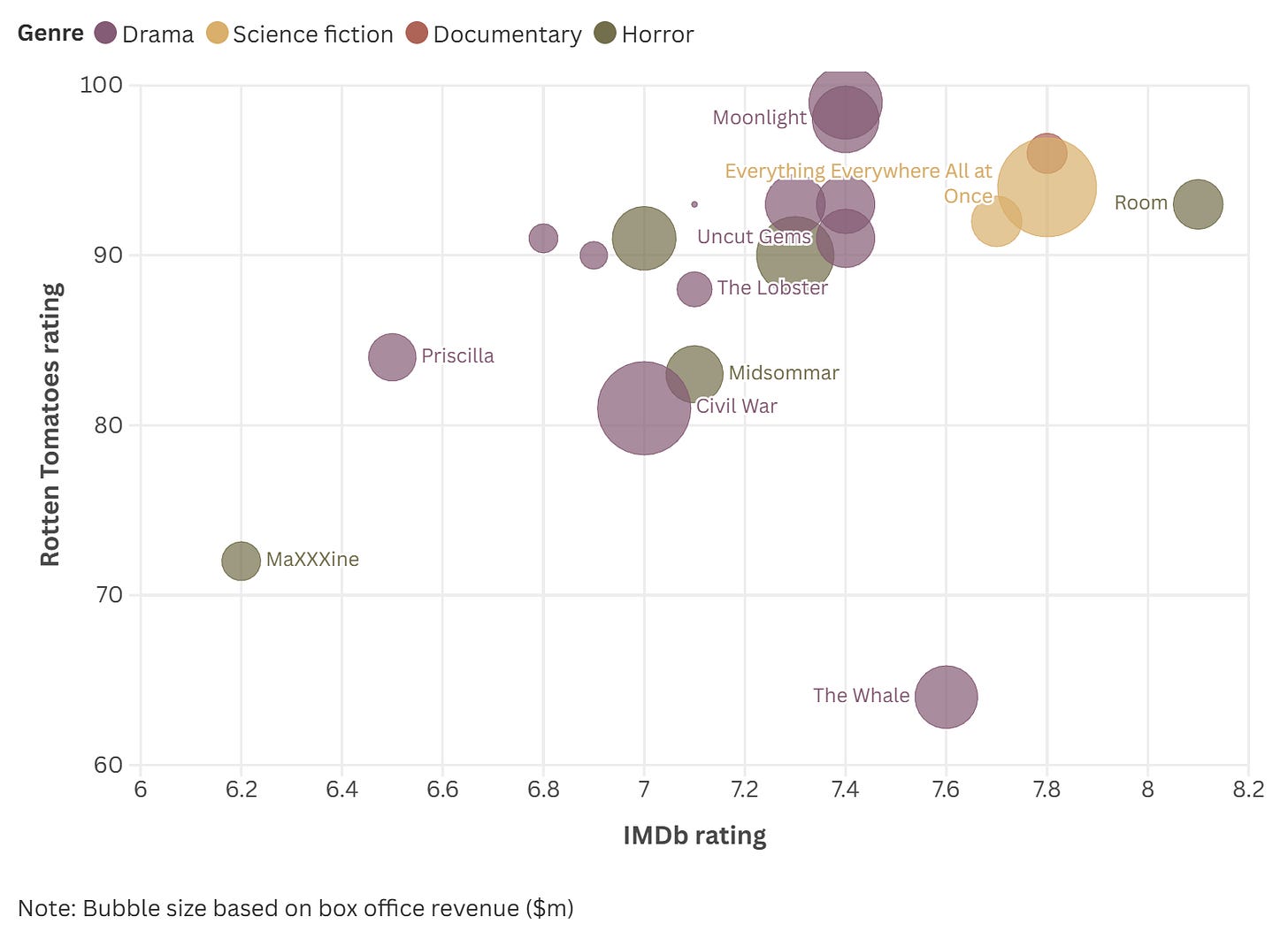

Our own chart below shows a snapshot of how a smaller set of 20 major films in their catalogue performed - in this chart, the bubble size relates to the box office revenue and the positioning of the bubble relates to the critical response (as determined by Rotten Tomatoes rating) and viewer response (as determined by IMDb rating).

20 key films in the A24 catalogue, mapped by critical and audience response

A recent, (very lengthy) article in media publication Dirt speaks to the position A24 holds for some movie fans and media industry players:

Fans interpret A24 as a champion of cinema that believes in the mass appeal of challenging projects. Detractors see a zeitgeist-chasing machine that hawks products rather than art. Meanwhile, everyone seems to be chasing what A24 has become synonymous with: brand loyalty. Just recently, an article in The Cut on Simon & Schuster’s new publisher, Sean Manning, described his aspirations as becoming the “A24 of books.” The unspoken implication: A24 stands for a slick, adult-oriented something, not just movies or TV shows but podcasts, literature, merch, and design principles. A24 is a world.

For a brisker take on what the fuss is all about, Vox has a decent 10 minute overview of their rise.

Society

Artificial intelligence and the humanities

Will the Humanities Survive Artificial Intelligence? | The New Yorker | Read essay

This essay in The New Yorker stood out amidst the slew of AI-focused prognostications that now surround us. The author D. Graham Burnett, a professor at Princeton, and Director of the School of Radical Attention, speaks to the role and purpose of the humanities today and in the future.

He identifies the humanities’ previous drift towards knowledge production as an approach and why that missed the point:

But factory-style scholarly productivity was never the essence of the humanities. The real project was always us: the work of understanding, and not the accumulation of facts. Not “knowledge,” in the sense of yet another sandwich of true statements about the world. That stuff is great—and where science and engineering are concerned it’s pretty much the whole point. But no amount of peer-reviewed scholarship, no data set, can resolve the central questions that confront every human being: How to live? What to do? How to face death?

The essay speaks to how things must now change given “knowledge production has, in effect, been automated”, and is ultimately hopeful about what remains:

But to be human is not to have answers. It is to have questions—and to live with them. The machines can’t do that for us. Not now, not ever.

And so, at last, we can return—seriously, earnestly—to the reinvention of the humanities, and of humanistic education itself. We can return to what was always the heart of the matter—the lived experience of existence. Being itself.

All that surfaces anew, because we are left alone with that. It alone cannot be taken from us.

And it is exhilarating. Also, at times, terrifying. It is, in the truest sense, sublime.